The invention of the camera inadvertently invented modern art

|

First Successful Photograph Taken

by Nicéphore Niépce in France 1826 |

The invention of the camera in the 19th century lead to great changes in art and society. Art, that is to say painting and sculpture, previous to the late 19th and early twentieth century had been considered a trade – artists in effect highly skilled tradesmen that were employed by the great and the good to make portraits, images of possessions and images for worship: The notion of the artist as an intellectual, of art being a medium of self expression and conduit of ideas did not exist. Art was for and controlled by the rich and powerful - the artist was in effect no different from a carpenter who might be commissioned to make furniture.

|

Mr and Mrs Andrews Gainsborough about 1750 |

|

| Las Meninas (Maids of Honor) 1656-57 Deigo Velasquez |

Where as painting had once been the slave to depicting reality through portraits, landscapes, still life, etc (although there had been religious and mythological pictures which were not meant to depict ‘real life’ they had been of clearly represented scenes and events), the invention of the camera had displaced this need and led painting to question it’s own function. Photography could now do exactly what its patrons where asking of art, to record reality, quicker and cheaper with more exacting results. Photography also had a certain cache in being excitingly new, modern and therefore fashionable – painting was soon seen as stuffy and old.

If painting was no longer the best – and certainly not the quickest – way of recording images of real things, what was it still useful for? The invention of the camera, or rather the kind of questions that the invention of the camera forced painters to ask of themselves, ultimately freed them from representing reality and allowed them to do something else instead – to concentrate on the act of painting itself.

Arguably, this process of questioning started with Edouard Manet and was continued by Claude Monet and the Impressionists. It was also fundamental to the work of Paul Cezanne, who was the forefather of Cubism, and to the Symbolists: Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Gauguin and Edvard Munch. The history of painting for the first half of the 20th Century can be seen as painting becoming increasingly aware of its own status as painting, and then realising the desire to free itself from all recognizable forms of subject matter.

|

| Monet |

This is painting’s journey toward abstraction, which although it had its roots in the 19th Century was a 20th Century phenomena. Picasso was important because he made the objects that were depicted in a painting subordinate to the picture as a whole. He used reality as a raw material, which he could manipulate and distort for his own purposes and ends, to help him to express whatever it was that he was trying to say.

|

| Picasso |

|

| Picasso |

The early 20th century saw an explosion of artistic exploration and the reinvigoration of many traditional media. Painting was reborn; it was now the excitingly new, modern: Avant-garde. The whole ideology of art had changed, it was now a purely intellectual pursuit and the artist had moved up the social ladder from tradesman to the wealthy to independent intellect equal to any other revered in western culture.

|

| Kandinsky |

|

| Mondrian |

Where as art grew and prospered, photography soon became stagnant. Photography was seen simply as means of recording, preserving the moment for prosperity. Though considered a marvel of the modern age, it was in no way considered an art form.

The problem of the photograph

Some nineteenth century painters had taken photographs and many had used them as aids, while some early photographers had been strongly influenced by paintings in their choice of subject matter, composition and indeed their whole conception of the photographic image. But despite the reiterated claim that photographs could be works of art, they were generally regarded as belonging to a distinct and inferior category, lacking the uniqueness and artistic prestige of painting, drawing or even printmaking which was usually one of a strictly limited numbered edition.

They were also, as a result of increasing mass production of easily manipulated cameras and the automatic processing of prints literally taken by millions of people, mostly amateurs, few of whom where aware of, and still fewer in sympathy with, the changes that had transformed art.

Moreover, other than a few like the Bragaglia brothers who wanted to explore photography's potential through exploiting its technical limitations, most self-consciously ‘artistic’ photographers clung to traditional ideas of composition in softly focused images. Even the main technical developments in the medium, facilitating greater sharpness of definition and instantaneity of vision, were equally out of phase with those in the other arts; tradition had been rejected wholesale as art moved closer and closer towards pure abstraction and the depiction of the internal rather than reflecting the external.

|

| Ansel Adams |

|

| Bragaglia brothers |

And then came along the Dada…

|

| Marcel Duchamp |

|

| Marcel Duchamp |

The First World War made a deep mark on western society and culture. It brought an end to a long period of material progress and prosperity in Europe. Some artists, as a reaction to the horrors of the war retreated from the adventurous and innovative explorations of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century towards more sedate work that explored traditional notions of aesthetic beauty – in a way an attempt at reestablishing the social values that existed before the war.

However, some reacted differently. For the Dadaists, the war gave a new point and urgency to the dissatisfaction of a society based on materialism and greed. They saw the war as being a requiem for the old society and their movement as the primitive birth of a new one.

Dada was christened in Zurich, but was essentially an international movement that spread quickly to other countries after the war. Dada was anarchic, nihilistic and disruptive. Dadaists mocked all established values, all traditional notions of good taste in art and literature, the culture symbols of a society based, they believed on greed and materialism and now in its death agony. The name Dada – a nonsense, baby talk word – means nothing, so was well suited to Dada’s negative nature. Dada even denied the value of art, hence its cult of non-art, and ended by negating itself: “The true Dadaist is against Dada”.

It is in this period that photography’s status as inferior to art would change. The underlying concept of rejecting all traditional notions of taste and desire to break all established rules – including the ones surrounding art - led them to embrace photography as a medium equal to the fine or high art of painting.

The Berlin Dadaists took collage, which had previously been explored as a part of cubist painting by Picasco and Braque through the use of newspaper text to create works of sophisticated visual wit, and exploited it for broader and more audacious purposes. Most importantly the Dadaist’s version of collage used photographic imagery. This became known as Photomonatge.

|

| Picasso - syhthetic cubism used collage first. |

Photomonatges were made up of fragments of found photographs, pieces of newsprint and so on, assembled in apparent disorder: In part these were a mockery of the popular bourgeois pastimes of gluing together cut outs for decorative and sentimental effect (decoupage), but it was also a means of subverting the values of fine art – the German word montage means ‘assembly’ as in mechanized industrial production – the use of photographic images was a direct attack on the notion of expressionism in art. Through the very nature of the medium they wanted to express the chaos of capitalist society during the war and its immediate aftermath.

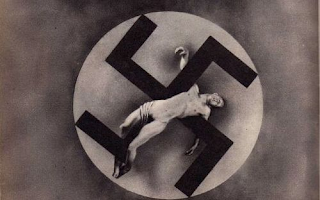

This method of working allowed its leading practitioners to create powerful political imagery – with Dada, the ideology of art moves from a preoccupation with the internal back to the external, though the notion of the external shifts from purely a reflection on aesthetic reality to a means of critiquing society: Hannah Hoch used images appropriated from fashion magazines mixed with tribal imagery from national geographic to create work that questioned western perceptions of beauty, the inequality of women and racism: John Heartfield used photomontage to confront enemies far greater than the complacent bourgeoise and expressionist painters. Heartfield made numerous anti – Nazi photomonatges which had a greater impact and made a stronger point than the standard political cartoon, simply because they where composed of photographs, direct images of reality carrying conviction even when the joins between one image and another where apparent. It is hardly surprising that photomontage was soon taken up for Nazi propaganda and commercial advertising – to falsify reality.

|

| John Heartfield |

|

| John Heartfield |

|

| Hannah Hoch |

|

| Hannah Hoch |

Man Ray and the Surrealists

|

| Man Ray Cadeau 1921 |

Whilst photographers such as Edward Weston who took sharply focused anthropomorphic images of plants, strangely shaped fruits, sections of vegetables and the human body which often looked abstracted was pushing the boundaries of the medium, it was a young artist involved in the Dada and later surrealist movements that really broke the boundaries and challenged the idea of photography as a lesser medium in artistic terms.

|

| Edward Weston |

Emanuel Rudnitsky, who called himself Man Ray was trained as a painter and was taken up by Duchamp and Picabia – the two key figures of the Dada movement – and moved from New York to Paris in 1921, the center of the art world at the time. Man Ray was initially a painter but he also photographed his friends and their artwork. Though it is disputed who really invented the photogram technique - William Henry Fox Talbot had made photogenic drawings by placing objects on photosensitive paper and Anna Atkins made the first photographically illustrated book "British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions in installments " using Sir John Herschel's cyanotype process, both in the mid nineteenth century, and László Moholy-Nagy, a member of the Bauhaus school and contemporary of Man Ray's was using the same technique extensively.

|

| William Henry Fox Talbot photogenic drawings |

|

| Anna Atkins |

|

| László Moholy-Nagy photogram |

However, Man Ray, arguably pushed the technique further than anyone else and he liked to claim the invention as part of his of own myth making: He said, on a sudden impulse one day in his dark room, he placed some objects on a piece of photographic paper, turned on the light for a moment and developed the print. This was a true Dadaist action, one that distrupted the conventions of photography – it even rejected the camera! He went on to make more of these camera less photographs – called Rayographs or photograms, selecting ordinary but disparate, opaque and translucent objects to be placed over paper and create images of strange ambiguity that where concrete and abstract at the same time. For the first time photography was not merely recording an objective truth - reality. In his photograms it is often impossible to say which planes of the picture are to be interpreted as existing closer or deeper in space. The picture is a visual invention in much the same way an abstract painting is: an image without a real-life model with which we can compare it.

|

| Man Ray Rayograms |

Dada soon burnt itself out, to be replaced by the Surrealist movement. Many of the key Dadaists were also involved in this new movement since it too was borne from a response to the crisis in western culture following the war. Surrealism had a more pragmatic approach though, and sought change not through rebellion and anarchism, but rather by means of intellectual revolution. Surrealism, founded by the poet Andre Breton, took the recent and revolutionary psychoanalytical writings of Sigmund Freud as a potential method of accessing a new kind of reality of the inner mind, a reality more intense and less controlled by the strictures of social life; to reveal a truth beyond the real, a kind of ‘sur-realism’. Man Ray went on to become one of the key members of the Surrealist movement.

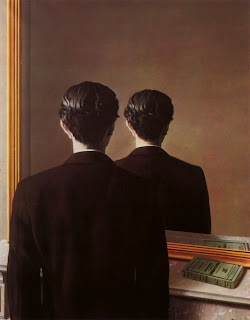

Early Surrealist work centered on the notion of the automatic – allowing the subconscious to create works that were not in the control of reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern: Man Ray later described his Rayographs – photograms- as being truly surrealist automatic works. Later surrealist works focused on the analysis of dreams outlined by Freud as a means of accessing the inner workings of the subconscious. In order to make effective ‘dream paintings’, which would allude to the condition of dreaming, a highly realistic and detailed style was adopted; the surrealists needed to manipulate reality in order to create an alternate, subjective, state. Realism – of a kind – was important in art again.

|

| Dali |

|

| Magrette |

|

| Magrette |

|

| Dali |

Man Ray utilized the basic property of photography; its ability capture a realistic image to make some of the most effective surrealistic images, much in the same way that the Nazi’s had adopted photomontage to promote a false reality.

He used a rich selection of various techniques including over and under exposure, shooting through fabric, superimposing images, painting with light and zeroing in on tiny details to manipulate reality into a fantastical image. In 1929 he discovered the solarisation process inadvertently and makes people look as though their faces are of aluminium. They become sort of sleek and metallic like the mascots on the front of the stylish, fast cars of the time. They become these super-people, also slightly inhuman, slightly robotic.

|

| Man Ray Solarisation |

Man Ray was inspired by his obsession with women and also began to explore female eroticism, evident in many of his photographs. He tried to create a Surrealist vision of the female form. His famous image Le Violon d’Ingres illustrates a vision of the cellist who holds his instrument like a woman between his legs. The simple copying of the sound-box apertures on to the back, allows the cellist’s dream to become a reality: the surreal transformation is complete.

|

| Man Ray Multiple exposures |

The Legacy

Arguably, its is Man Ray’s work with photography in the creation of a surrealist image that changed the status of photography from what was seen as a machine-like process manufacturing objective truths purged of subjectivity and emotion to that of a creative and expressive art form. For Man Ray, the camera was not a machine for making documents but an instrument for exploring dreams, desires and the unconscious mind, just as conventional forms of fine art, such as painting, were in the ideology of modern art. The fact that he became one of the principal photographers for Harper’s Bazaar, meant that the public soon became familiar with his work as representing surrealist art, thus helping the establishment of the photographic image as a legitimate art form.

It is not only Man Ray’s process oriented art-making and versatility that has influenced younger generations artists to break the boundaries between disciplines. Most importantly, it is the idea that the photograph can be more than pure documentation, but rather reveal a subjective reality (regardless of whether it is manipulated or not), as first explored within the Dada and Surrealist movements that eventually lead to the acceptance of photography as a fine art medium.

Though the photograph was by no means considered to be a major medium in the cannon of art until the late 20th century, contemporary artists no longer see photography as being a lesser from of expression. Many artists who work with photography have been influenced by Man Ray and the Dadaists, from obvious influences such as the collage work of John Stezaker; the abstracted photographs of Wolfgang Tilmans to the not so obvious subjective realities of Philip Lorca Dicorcia and William Eggleston's automatic approach.

|

| Philip Lorca Dicorcia |

|

| John Stezaker |

|

| William Eggleston |

|

| Wolfgang Tilmans |

|

| Joel Peter Witkin |

|

| Tim Walker |

|

| Gregory Crewdson |